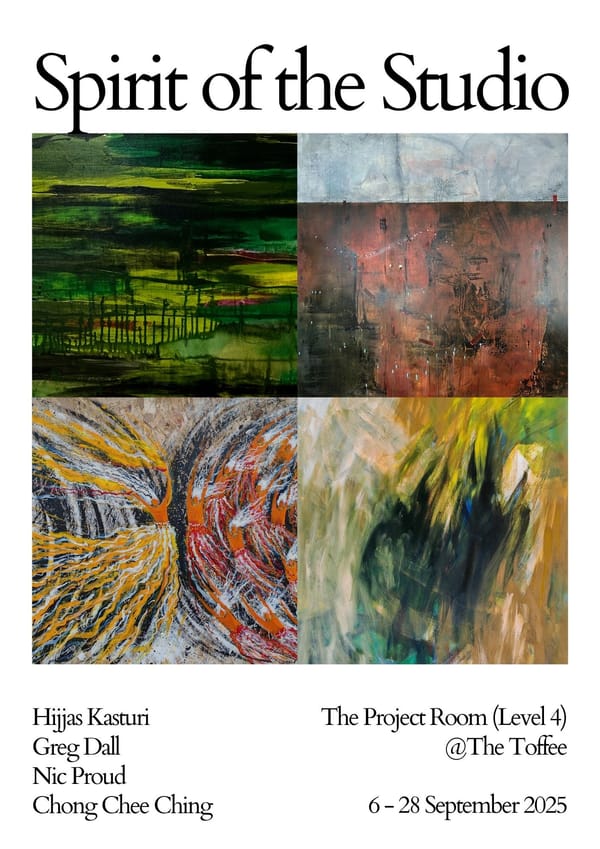

Observing the Subjects of History: Chang Yoong Chia’s Mythological Worlds

Co-written with Lim Sheau Yun. Exhibition essay for Thinking Like A Mountain, Chang Yoong Chia's solo at CULT Gallery from 23 November 2024-19 January 2025.

In the town of Tangkak in Johor, Gunung Ledang, also known as Mount Ophir or 金山 (Golden Mountain), is a singular presence. As you gaze at the mountain from the main road of shop lots, it stands as a constant, lone pyramid. There is no visible mountain range around it, and thus it falls as sharply as it rises, almost architectural in its quality. When clouds arrive, they do not so much cover Gunung Ledang as much as they engulf it, and it vanishes like a disappearing act. It’s easy to imagine what the ancients must have seen—a presence so enchanting it seemed beyond time, a mountain spirit woven from space and light. From his Tangkak home, artist Chang Yoong Chia has awoken every morning to greet this summit.

In 2021, one day before the state of emergency was declared, Yoong Chia and his partner, Ming Wah, moved from Kuala Lumpur to Tangkak. They only had one friend there, but had long been desperate to get out of the city – what better timing than when the world was about to shut down.

Two years ago, after seeing Gunung Ledang every day, Yoong Chia and Ming Wah began a major piece of research. Thinking Like A Mountain, Yoong Chia’s 2024 solo exhibition at Cult Gallery, is but the first step in what they envision as a larger project, an entire cosmic realm akin to Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman. Here, Puteri Gunung Ledang is cast as a character within a sprawling mythological universe that spans centuries, starting before the Melaka Sultanate and extending into the 1980s. She interacts with figures like Hang Li Po, Alfred Russel Wallace, Ratu Kidul, and others, as they traverse worlds both historical and otherworldly. Each character is imagined in moments of interaction, contemplation, and transformation, fleshing out not only their personalities but also their physicality—the way they move, dress, age, and exist in this evolving world. Each piece becomes a character in an ongoing conversation, with Yoong Chia as imagineer, inviting the land of the Malay peninsula and its myths to speak.

Gunung Ledang and the Potence of Mythology

The myth of the princess of Gunung Ledang is familiar to most Malaysians, diffused in our imagination of place and time. Let us rehearse it: Sultan Mansur Shah of the Malacca Sultanate demands a wife who shall surpass all other wives. He was already married to a princess of China, Hang Li Po, and a princess of Java, Princess Radin Galah Chandra Kirana of the Majapahit Empire. But he wished for more. Discontent with a wife of the Nusantara (the local), a princess from the Middle Kingdom (the foreign), he wished for a woman of the magical mountain (the otherworldly). He had his eyes on the fairy princess, Puteri Gunung Ledang. To that end, he dispatched his loyal servants, Hang Tuah and Tun Mamat, and a retinue of other subjects to fetch her for marriage. After enduring a harsh climb, Tun Mamat encountered a beautiful garden, where he conveyed the Sultan’s proposal to four women. Once they received the message, the women vanished.[1]

Later that night, an old woman appeared before Tun Mamat. She conveyed the princess’s betrothal wish: a bridge of silver and a bridge of gold, seven trays of mosquito hearts, seven trays of the hearts of mites, a vat of water from dried areca nuts, a vat of virgin maidens’ tears, a cup of the Sultan’s blood, and, above all, a cup of his son’s blood. Tun Mamat returned to Malacca and presented the Sultan with these demands. The Sultan, humbled, was able to provide all the gifts except one: he would not draw blood from his own son.

Like all myths, the story of Puteri Gunung Ledang has been interpreted as many times as it has been told. Some see the Sultan’s refusal to provide his son’s blood as a parent's enduring love for a child, a love that transcends all other ambitions. Others see the Sultan’s humbling as a cautionary tale, that one should not be overly egoistic. To feminists, Puteri Gunung Ledang’s legendary demands speak to a denial of patriarchal power structures and as unyielding as the mountain itself. She embodies a sovereignty beyond political authority, a figure who, through her wit and canniness, claims her autonomy.

The potency of myth is in its narrative ability to enable interpretation and moral tales, yet also transcend these easy lessons. The same instinct is at the heart of Thinking Like A Mountain, to tell stories not easily collapsed into caricature. By collapsing linear time and placing in dialogue figures from both mythology and history, Yoong Chia presents a narrative landscape that examines the stories we tell ourselves, the stories that have produced the nation we know today as Malaysia.

“We are stardust.”

The phrase “Thinking Like a Mountain” originates from the title of early ecologist’s Aldo Leopold’s eponymous chapter from his book, A Sand County Almanac.

Leopold writes:

“In those days we had never heard of passing up a chance to kill a wolf. In a second we were pumping lead into the pack…we reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realised then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes- something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sense that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.

We all strive for safety, prosperity, comfort, long life, and dullness. The deer strives with his supple legs, the cowman with trap and poison, the statesman with pen, the most of us with machines, votes, and dollars, but it all comes to the same thing: peace in our time. A measure of success in this is all well enough, and perhaps is a requisite to objective thinking, but too much safety seems to yield only danger in the long run. Perhaps this is behind Thoreau's dictum: ‘In wildness is the salvation of the world.’ Perhaps this is the hidden meaning in the howl of the wolf, long known among mountains, but seldom perceived among men.”[2]

Leopold here calls for us to consider the consequences of human actions, to attend to epochal, mountainous time beyond the span of our relatively short, human ones. In Thinking Like A Mountain, Chang Yoong Chia extends Aldo Leopold’s ecological philosophy by embracing pre-colonial, animistic traditions that view nature as imbued with spirits. While Leopold emphasised understanding the interconnectedness of temporality and ecosystems, Yoong Chia builds upon this human-nature relationship by reintroducing a third dimension: the mythical. This pre-colonial episteme allows us to see the mountain not merely as a physical entity, but a living system inhabited by deities and ancestral spirits.

As James Huntley Grayson notes in his study of Korean yo-sansin (female mountain spirits), these figures are often “guardians of natural places” and represent a “close relationship between the people and the mountain that dominates their lives.”[3] Similarly, in Thinking Like A Mountain, Yoong Chia brings to the fore spirits who emerge from, and are identified with, specific places: Puteri Gunung Ledang, Hang Li Po of the well in Malacca, Ratu Kidul of the Southern Sea. They are connected to an ethic of place, establishing the natural world as both spiritual presence and sovereign force beyond human control.

Thus, for Yoong Chia, myth is a domain in which the forces of history, ecology, and imagination converge. In Study for Puteri Gunung Ledang, Redux: Supernova (2023), Yoong Chia explores the symbolism of gold—an element tied to Gunung Ledang not only in myth but in historical accounts of early Chinese and British mining in Malaya. Rendered in graphite, the swirling textures recall nebulae as they surround a central feminine figure, her spectral form emerging from a primordial chaos. Gold, Yoong Chia notes in our conversation, originates from stardust, and is forged in supernova explosions and scattered across the universe. Gold is not merely something to be mined or possessed: it is a relic of creation itself. Gunung Ledang, called 金山 (Golden Mountain) in Chinese, becomes a place of mystique, where history and cosmic origin converge. To borrow a lyric from singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell’s Woodstock (1970): “We are stardust, we are golden.”

Naturalism, Perception and a Political Aesthetic

On one hand, Yoong Chia is interested in land spirits that have endured since the cosmos. On the other, there are characters who are rovers and travellers, whether brought by the sea, like Chinese deity Guan Gong, or searching for a tale of faraway, like the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913). Yoong Chia displays a keen sympathy to the latter archetype, the lone discoverer who leaves a paper trail of his work. Wallace, who climbed to the summit of Gunung Ledang with “six Malays to… carry our baggage,” was less than enraptured by the sight of Gunung Ledang: “In a distant view a forest country is very monotonous, and no mountain I have ever ascended in the tropics presents a panorama equal to that from Snowdon, while the views in Switzerland are immeasurably superior.” Of far more interest to the English naturalist were the flora and fauna, including “the pitcher plants which were most remarkable,” “those splendid ferns Dipteris Horsfieldii and Matonia pectinata,” and the “great Argus pheasant.”[4]

In 1855, Wallace composed the essay “On the law which regulated the introduction of new species,” also known as the “Sarawak Law,” at the estate of Sir James Brooke[1] , which was located at the foot of Mount Santubong. The Sarawak Law would eventually lead Wallace to co-develop an evolutionary theory of natural selection, which was presented on July 1, 1858, at the Linnaeus Society in London alongside Charles Darwin’s thesis, “On the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection.” The roots of the method of Darwin and Wallace lay in careful observation: to record was to narrate, to impose order on what they viewed as the bewildering chaos of the jungle.

The Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus, often referred to as the “father of taxonomy,” laid the groundwork for this method in the 18th-century. His Systema Naturae provided a framework for classifying the natural world, organising it into hierarchical categories that could be understood, named, and controlled. Key to this taxonomical method was the use of careful, precise and sustained observation, which would allow the naturalist’s powers of perception to reveal and organise common, or divergent, characteristics between organisms, which could then be placed into taxonomic classifications. For Linnaeus, this process required both the body and the mind to work in tandem. As Daston and Galison write, “The eyes of both body and mind converged to discover a reality otherwise hidden to each alone.”[5]

It is no coincidence that figures like the Jesuits or Stamford Raffles all viewed themselves as great observers of the world. To bring civilisation pre-supposed a lack of civilisation, and thus required narratives to justify their mission. Raffles, rather infamously, was known to have deeply resented his station in Singapore and expended every effort instead to engage with his ‘real brethren’ such as French naturalists Alfred Duvaucel and Pierre Médard Diard, sneaking off whenever he could to work on his real passion: The History of Java, which was published in 1817. Incidentally, much of what we know of the Sejarah Melayu too was dictated by Raffles, for the version he acquired in his process of cataloguing, coded Raffles Manuscript 18, is considered the most authoritative version from which most of our understanding today descends. In this context, observation was both an act of discovery and domination, a means of creating knowledge that simultaneously claimed ownership over the observed world.

This is the intellectual and political legacy that Chang Yoong Chia interrogates and reimagines in Thinking Like A Mountain, where the act of observing—whether a mountain, a myth, or a story—becomes a way to unsettle, rather than reinforce, dominant narratives of power and control.

In Decalcomania IV: Wallace Ascends Mount Ophir (2023), Yoong Chia directly addresses Alfred Russel Wallace’s account of his ascent of Mount Ophir, with a torn scrap of text quoting his journal: “After which the ascent was steeper and the forest denser until we came upon the Padang-batu, or stone field, a place of which we had heard much, but could never get anyone to describe intelligibly.” In the sprawling painting, Yoong Chia builds a dense and tactile surface, with a layered, almost geological quality of canvas, where the ridges and grooves of paint mimic the craggy, overgrown terrain of the mountain. Wallace himself is depicted as a diminutive figure, almost swallowed by the landscape. Dwarfed by the scale and complexity of the mountain, an ecosystem brimming with hidden life, oversized leaves, curling ferns, and shadowy recesses that suggest unseen creatures, Wallace’s attempts to classify and know the mountain are defied.

It is to this end – that of resisting easy, categorical forms of knowledge – that Yoong Chia’s use of the technique of decalcomania takes on a political aesthetic. Decalcomania is a surrealist method pioneered by Max Ernst, where paint is pressed between two surfaces – two panes of glass, two planes of wood – and then peeled apart to create unpredictable, never-fully-controllable patterns. The artist’s job is then to respond to these forms with their aesthetic impulses, allowing a pre-rational form of knowledge to take over in the act of painting. For Yoong Chia, decalcomania becomes an interrogation of the act of observation itself, reconfiguring Gunung Ledang not as an object to be mapped or a summit to be conquered, but as an agent of its own telling.

Thinking Like A Mountain marks an evolution in Chang Yoong Chia’s artistic practice. Yoong Chia’s earlier pieces, particularly his mosaics made from thousands of tiny stamps, were rooted in a meticulous process—a kind of painstaking, ritualistic dialogue with material. The stamps themselves were sourced with intention, their images carefully chosen for their symbolic weight. Cutting each one out and assembling them into tight compositions became an act of both creation and delimitation. With decalcomania, Yoong Chia introduces a new kind of dialogue—one that embraces chance and spontaneity. Unlike the strict, self-imposed constraints of his stamp works, decalcomania creates space for unpredictability, for patterns to emerge beyond the artist’s control. It is as if Yoong Chia is allowing material itself—the paint, the surface, the act of pressing—to become an active collaborator in his storytelling.

This shift to decalcomania is no mark of laxness or a retreat from his characteristic rigour. For this project, Yoong Chia’s approach has taken a deeply scholarly turn; he immerses himself in these figures’ lives, unearthing every layer of their stories and drawing from an array of sources—folklore, the Sulalatus Salatin (a.k.a. Sejarah Melayu or Malay Annals), the Suma Oriental, popular media, academic studies, and graphic novels. For him, it is itself a quest to understand these figures, and to that end, he treats what narrative crumbs we have today with the rigour of an archivist. Yet, there is a deep infidelity in his work, weaving into this research the insight of a storyteller. One might even argue that since the Sulalatus Salatin and the Suma Oriental are conveying tales–fact mixed with fantasy–that this is a more faithful, more truthful interpretation of their strategies. Rather than a naturalist method of classifying, Yoong Chia views this project as an “opening up,” a way of inviting viewers to experience these figures not as static representations but as participants in an unfolding story.

“Seizing hold of a memory”

In Ophir the Great Mountain (2023), Chang Yoong Chia uses gouache on a single leaf to evoke the living spirit of Gunung Ledang. An actual leaf, gathered during Yoong Chia and Ming Wah’s hikes to the waterfall of Taman Negara Gunung Ledang—thin, brittle, its veins still visible—forms the foundation of the work. The central figure—a woman—is both human and elemental, her body woven into the landscape of Gunung Ledang. Her wide, almost mournful eyes meet yours, and her hands, drawn with a reverent sensitivity, seem to simultaneously clutch and release the space around her. The woman’s hair flows like vines, threading her into the forest below. Her gaze is steady and unyielding.

Below her, the leaf transforms into a dense, living forest. Tiny details—birds caught mid-flight, the glimmer of insects on leaves—reward slow observation, pulling the viewer deeper into the microcosm of Gunung Ledang. The mountain’s trees extend downward into the leaf’s stem, merging with its veins. Yoong Chia’s sensitivity to detail and his choice of medium is a call to observe, to be drawn into its rhythms, to see the mountain as he does: alive, storied, and sacred.

Yoong Chia’s ultimate project is one of reclaiming myth and emphasising the importance of place in a post-colonial situation. In the age of increased political polarisation and the Anthropocene, Yoong Chia reaches back in time to syncretise a speculative world that reaches from the multiple threads of cultural influence upon the Malayan peninsular. This is a world in which we are intimately familiar, made strange and enchanted once more. In the words of Walter Benjamin, “to articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was.’ It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.”[6]

[1] Cheah Boon Kheng and Abdul Rahman Haji Ismail, eds., Sejarah Melayu, Ed. Rumi baru, Reprint, no. 17 (Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1998).

[2] Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972).

[3] James Huntley Grayson, “Female Mountain Spirits in Korea: A Neglected Tradition,” Asian Folklore Studies 55, no. 1 (1996): 119–34, https://doi.org/10.2307/1178859.

[4] “Wallace, A. R. 1869. The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-Utan, and the Bird of Paradise. A Narrative of Travel, with Studies of Man and Nature. London: Macmillan and Co. Volume 1.,” accessed November 17, 2024, https://darwin-online.org.uk/converted/Ancillary/1869_MalayArchipelago_A1013.1/1869_MalayArchipelago_A1013.1.1.html.

[5] Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, Objectivity (Cambridge, MA: Zone Book, 2010).

[6] “Walter Benjamin On the Concept of History /Theses on the Philosophy of History,” accessed November 17, 2024, https://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/CONCEPT2.html.